In the 19th and 20th century Australian horses were sold for military purposes to the Indian Army and also to other countries. The Indians called them ‘Walers’ because they came from New South Wales, which at that time covered most of mainland Eastern Australia. The name stuck, even after federation, when the horses were being recruited from other states as well. They were not a recognised breed but rather Australian stock horses that had been bred for the harsh Australian outback conditions.

The first seven horses came on the First Fleet with others following on later ships. Originally from Britain, the horses were bred in Australia in the Hunter Valley. They were known for their speed, strength and stamina in tough conditions.

Horses were the major means of transport for the troopers in the desert. At any point there were 13,000 horses serving the troops in the Middle East. They not only carried soldiers to the battle front, but also carried mail, pulled heavy equipment such as guns, drew ambulance wagons and carried the wounded.

Eight thousand horses were transported with the first troops but due to the rough seas and humid tropical weather, 220 of them died before they even touched the shores of Egypt. Many of these had caught pneumonia. A total of six million horses died during the course of the Great War.

Caring for the horses was very important. They had to be groomed daily – rubbed and massaged with a metal-toothed comb called a currycomb, then brushed with a stiff brush to remove the dirt and finally a softer brush over the body. The mane and tail had to be brushed to remove all the tangles, burrs and grasses. Their hooves needed to be cleaned of dirt and stones and polished. The horses had to be regularly exercised to keep fit and given endurance training to build stamina. All of this process built the relationship between man and beast. This trust was crucial to their success in the drama of warfare.

Caring for the horses was very important. They had to be groomed daily – rubbed and massaged with a metal-toothed comb called a currycomb, then brushed with a stiff brush to remove the dirt and finally a softer brush over the body. The mane and tail had to be brushed to remove all the tangles, burrs and grasses. Their hooves needed to be cleaned of dirt and stones and polished. The horses had to be regularly exercised to keep fit and given endurance training to build stamina. All of this process built the relationship between man and beast. This trust was crucial to their success in the drama of warfare.

They also had to be highly trained so they would not react at the noise of gun shots, artillery and aircraft. They had to obey the slightest hand on their neck or quiet word from their master, as silence meant life-preservation at times. There were veterinary surgeons and specialist horse handlers that went with the troops. Two of the horse handlers were an aboriginal tracker named Jackie Mullagh, and Banjo Paterson, better known for his writing and lyric bush poetry. Their job was to break in the newly-arriving horses and get them ready for the battle front. They also cared for the reserve horses.

The most heart-breaking part of the war for many of the ANZAC Horse men was the decision that no horses were to come back. The Australian government had quarantine concerns and was not prepared to go to the expense of bringing the animals home. The best horses went to Britain for breeding or as cavalry. Others were sold to the British army and went on to serve in India. Some were sold to Belgian farmers or as horsemeat. All horses over the age of 12 and those that were sick or injured, were systematically shot.

136,000 Walers were sent from Australia. Only one returned.

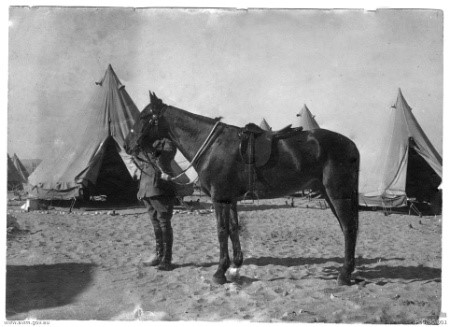

In the Sinai, the ANZACs constituted four fifths of the total mounted troops. The Australian War Memorial records that 136,000 Walers were sent from Australia and only one returned. It was the dying wish of Major General Sir William Bridges that his horse, Sandy, be repatriated to Australia. Bridges, the commander of the 1st Australian Division in Gallipoli, was killed by sniper fire. He had founded the military college at Duntroon. His wish was granted. In 1918, Sandy sailed from Liverpool and spent the rest of his days at the Remount Centre in Maribyrnong.

In the Sinai, the ANZACs constituted four fifths of the total mounted troops. The Australian War Memorial records that 136,000 Walers were sent from Australia and only one returned. It was the dying wish of Major General Sir William Bridges that his horse, Sandy, be repatriated to Australia. Bridges, the commander of the 1st Australian Division in Gallipoli, was killed by sniper fire. He had founded the military college at Duntroon. His wish was granted. In 1918, Sandy sailed from Liverpool and spent the rest of his days at the Remount Centre in Maribyrnong.

The same was true for the New Zealanders. Only one horse came home for them also – a mare named Bess.

In many cases, the horses had saved lives. There are stories of the lead horse refusing to take another step in the dark night fog. The soldiers then discovered that there was a plummeting ravine ahead that they had not seen. Some injured troopers’ lives were saved by their sensitive horses that knew their need and carried them back to base.

The ANZACs were so disgusted with how the local people flogged and abused their animals that they preferred to shoot their horses themselves rather than risk having them mistreated after the war.

Trooper ‘Bluegum’ (Major Oliver Hogue) summed up his feelings in rhyme.

I don't think I could stand the thought of my old fancy hack

Just crawling round old Cairo with a 'Gyppo on his back.

Perhaps some English tourist out in Palestine may find

My broken-hearted Waler with a wooden plough behind.

No: I think I'd better shoot him and tell a little lie:--

"He floundered in a wombat hole and then lay down to die."

May be I'll get court-martialled; but I'm damned if I'm inclined

To go back to Australia and leave my horse behind.1

It was a sad end for their faithful friends who never volunteered their services but went far beyond their call of duty.

Endnotes:

- Perry, R., Bill the Bastard, Allen & Unwin, 2012, 265

Pictures:

- Best Mates - Ray Kuhn and Phantasia. Painting by Jennifer Marshall www.lighthorse.com.au

- Sandy – Major General Sir William Throsby Bridges, KCB, CMG, Commander of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) and of the 1st Australian Division in 1914-1915, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/P05290.001