The surrender of a city is a complex matter politically, especially considering the fact that Britain had made promises to both the French and the Arabs to keep them on their side, but these were somewhat contradictory.

T.E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) was a military intelligence officer with the British army who had been working with the chief Arab leader of the Arab irregular army, Emir Feisal. This group of tribes were not keen on the Ottoman rule and Lawrence had convinced them to back the British initiative. He had promised in return to let Feisal’s Hashemites rule in Damascus.

In the 1962 epic movie, Lawrence of Arabia, we have been led to believe that the Arabs were the first to enter Damascus. Was this true, or was this just ‘saving face’ in an awkward situation?

When the Allied troops conquered the city, politics demanded that the ‘honour’ of the handover of the city must be given to the Arabs. Honour is the most important value in Arab culture (not truth as in the West), so this would appease them, despite the fact that the mandated control would eventually be given to the French.

Seeing that the fall of the city was inevitable, Turks and Germans fleeing the city in the days before the surrender, but were gradually being cut off as the Allied armies were arriving and blocking the escape routes to the south and west. On the night of September 30th, the city was in tumult, being troubled by factional fighting and disturbances, causing blockages in some of the narrow laneways that went through one of the oldest cities in the world.

Seeing that the fall of the city was inevitable, Turks and Germans fleeing the city in the days before the surrender, but were gradually being cut off as the Allied armies were arriving and blocking the escape routes to the south and west. On the night of September 30th, the city was in tumult, being troubled by factional fighting and disturbances, causing blockages in some of the narrow laneways that went through one of the oldest cities in the world.

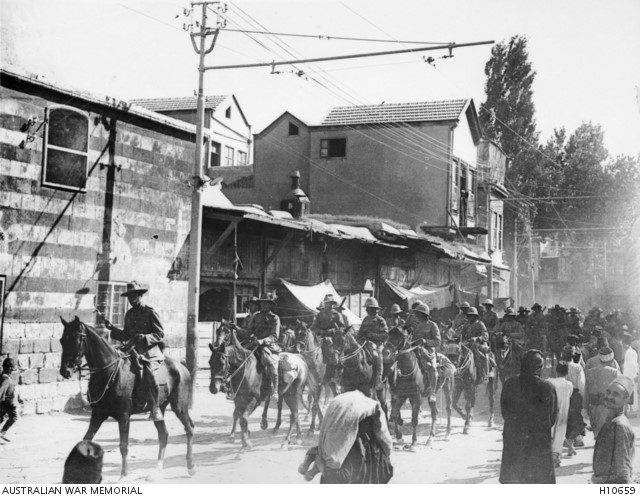

The ANZAC troops had been halted on the outskirts of Damascus, in preparation for the formal handover, but the 3rd Light Horse Brigade was given the task of cutting off the road to the north of the city which led to Homs and Aleppo. The quickest way to get there was straight through town. At the forefront of this Brigade was the 10th Light Horse Regiment led by Major Timperley and his second-in-charge, Captain Arthur Olden. After a sleepless night, at 5 am on October 1, 1918, they began to move into the city, arriving in the city square before 7 am. The commanders entered the Serai (Town Hall), where the city administrators were meeting. Olden demanded protection for his troops, and in return promised that they would not harm the populace. Governor Emir Said Abd el Kader, who had only been instated the night before, replied, “In the name of the civil population of Damascus, I welcome the British army”.1 Olden then got this assurance formally in writing, then left to continue their ride through town to block the Homs road. This was made difficult by the exuberant crowds now eager to welcome the liberators. They then went in pursuit of the retreating Turks and Germans towards Aleppo, leaving others to take charge of the city.

Barely had they cleared the way, than Lawrence arrived with a few of the Arabs with a flamboyant entry riding wildly through the town. About 8.30 am General Chauvel drove in for a meeting to decide the city’s future. The British agreed that Shukri Pasha el Ayoubi should act as the temporary military governor, so Said’s term was very short-lived. In fact he was imprisoned a few days later. Unaccustomed to large scale administration and with 20,000 Turkish prisoners, numbers of whom were sick, as well as their own population, not to mention the political upheaval taking place, the city dissolved into chaos.  Other Arab tribes and Bedouins also arrived looking to profit from the disorder. On October 2nd Chauvel decided to make a march through town to quell the riots, after which the city calmed down. The British began to hand out food rations as the negotiations about the longer-term future of the city continued. Feisal’s dream to rule over a large area of Syria was curtailed and even then he was only to administer Syria under French governance. In the meantime, Lawrence returned to England.

Other Arab tribes and Bedouins also arrived looking to profit from the disorder. On October 2nd Chauvel decided to make a march through town to quell the riots, after which the city calmed down. The British began to hand out food rations as the negotiations about the longer-term future of the city continued. Feisal’s dream to rule over a large area of Syria was curtailed and even then he was only to administer Syria under French governance. In the meantime, Lawrence returned to England.

The Australian War Memorial has a copy of Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom (which he later admitted was not always based on fact). In January 1936, Chauvel wrote a letter to the Director of the War memorial noting some of the inaccuracies in the book. One of these was Lawrence’s account of the entry to Damascus.

With reference to Lawrence's claim that 4,000 Rualla tribesmen had entered Damascus during the night of 30 September 1918, he says:

If any of Feisal's followers did get in during the night, they were unrecognisable as such to the enemy or ourselves . . . I am personally of the opinion that the first of the Arab forces to enter Damascus were those who followed Lawrence in and, by that time an Australian Brigade [the 3rd Light Horse Brigade] and at least one regiment of Indian Cavalry had passed right through the city.2

Endnotes:

- Gullett, H., Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918. Vol V11, Sinai and Palestine. Angus and Robertson, 1923, Page 761

- https://www.awm.gov.au/blog/2006/11/14/the-taking-of-damascus/

References:

https://www.awm.gov.au/blog/2006/11/14/the-taking-of-damascus/

https://www.awm.gov.au/blog/2007/01/15/seeing-is-believing-more-on-the-taking-of-damascus/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capture_of_Damascus_(1918)

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1572464/Australia-claims-it-captured-Damascus-first.html

Pictures:

- The narrow streets of Damascus – J. Curry

- Australian War Memorial https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/H10659/ Lieutenant General Sir Harry Chauvel, Commander in Chief, Desert Mounted Corps riding through Damascus at the head of the Australian Army Light Horse.