In desert warfare, it is all about water for horse and rider. To break the defence line, when the opposition has the water and you do not, means you have to win, you have to win quickly and you have to capture the water supply intact. British scouts went ahead, surveyed wells and marked maps with the quality and amount of water they could supply. Beersheba was marked ‘unlimited’. At the ancient wells of Abraham lay the elusive water they craved, but it needed the courage of David to defeat the entrenched Goliath to capture the city. In preparation for the troops, engineers had located, cleaned up and prepared available wells along the route through the dry river bed of Wadi Ghuzze. It was now the end of the dry season.

General Allenby conceived a plan, to deceive the enemy that they would be attacking Gaza while the main force was to take Beersheba in the east before cutting across behind Gaza. Gaza was heavily bombed from the sea for a few days before the attack. They had also deliberately dropped a note detailing the impossibility of an attack on Beersheba due to lack of water, which the Turks ‘found’ and believed.

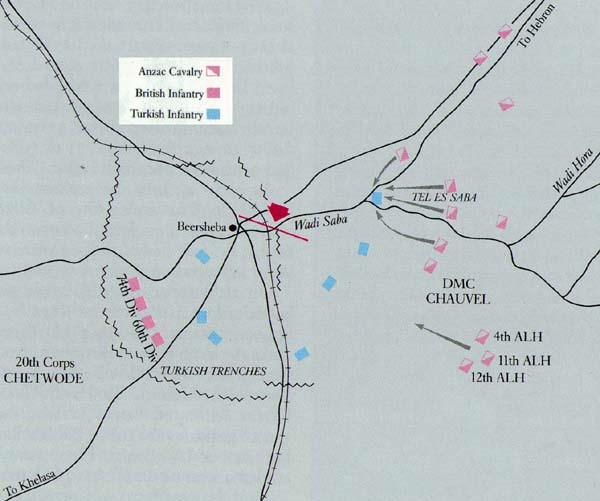

The troops set off at night from Shellal with three days’ supplies and tried as best to hide and rest by day. After three sleepless nights trekking through the desert with little water (many horses went 48 hours and some up to 60 hours without water), they arrived at Beersheba. The bombardment started at dawn with three British divisions attacking the Turkish trenches on the southern side.  They fought hard and by early afternoon they had had captured their given objectives, suffering 1,151 casualties in the process. Meanwhile, the 2nd Light Horse Brigade successfully blocked the Hebron road to the north to cut off the escape route and prevent reinforcements arriving.

They fought hard and by early afternoon they had had captured their given objectives, suffering 1,151 casualties in the process. Meanwhile, the 2nd Light Horse Brigade successfully blocked the Hebron road to the north to cut off the escape route and prevent reinforcements arriving.

However, the high hill of Tel el Saba – the original site of the ancient city – was still in Turkish hands allowing the snipers to rain bullets down from above. Capturing this was vital for what was to follow. The New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade, with some Australian Light Horse reinforcements added later, fought hard on foot through the Turkish defences from mid-morning until Tel el Saba was finally captured in mid-afternoon about 3pm.

It was crucial to have the city by nightfall and time was running out. General Chauvel, now overall commander of the Desert Mounted Corps, needed to take decisive action. There was only about an hour of daylight left. As Gullett says, “surprise and speed were their one chance”1. He ordered the ANZAC 4th Brigade to line up and charge. Nothing else could work at this late stage. This had never been attempted by Light Horse. As the jacket cover for The Light Horsemen movie says, “They did not know it was impossible, they just obeyed orders.”

The 4th and 12th Light Horse regiments (800 horsemen), with the 11th following in reserve, set off across 6 km of open ground in the full face of Turkish artillery and rifle fire, first at a trot, then a canter and finally a full-blown charge. They wielded their bayonets and yelled as they went. The Turkish gunners had their guns set for 1,500 metres but were ordered not to fire until the troops dismounted, as they always did – at least up till now. Faster and faster the horses approached. By the time the Turks realised that the horses were not going to stop, they could not wind down their heavy machinery fast enough. The shrapnel flew over their heads and exploded behind them. The British artillery took care of the source of those initial machine guns. Of more concern were the bombs dropped from the German aircraft above. With bombs exploding and rifle fire pinging around them, now in a total adrenaline rush, many riders simply jumped the trenches and continued on into town. Never had any of them experienced a ride like this one! Some dismounted and began fighting hand-to-hand with the stunned Turks in the trenches. Some were hit and fell to the ground, injured or dead. The New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigade and the British Yeomanry Brigade provided back up and other reserve troops began swarming on the city. The impossible breakthrough was accomplished, but the danger was not yet past.

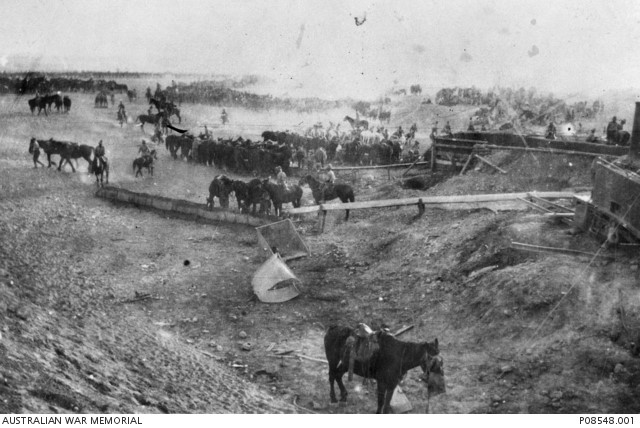

The precious water wells had been mined and the German officers were in the process of blowing them up. They might yet just have the last laugh. Trooper ‘Scotty’ Bolton managed to follow the wires, stop the German officer at the switchboard and save all the wells except two or three. By 7 pm 60,000 men and 100,000 animals had descended on Beersheba. They needed 1,800,000 litres of water! It would just take great patience for all the parched animals and humans to drink their fill.

The precious water wells had been mined and the German officers were in the process of blowing them up. They might yet just have the last laugh. Trooper ‘Scotty’ Bolton managed to follow the wires, stop the German officer at the switchboard and save all the wells except two or three. By 7 pm 60,000 men and 100,000 animals had descended on Beersheba. They needed 1,800,000 litres of water! It would just take great patience for all the parched animals and humans to drink their fill.

The gamble had paid off. They had captured the life-giving ancient wells and were now in a strategic position to move on to Jerusalem. It was not only a military victory; it was also a morale booster for the Allied troops and a demoralising defeat for the Turks. The upper hand was now plainly in Britain’s favour.

Ion Idriess, from the 5th Light Horse, who watched the scene unfold, describes what he saw that day:

Then someone shouted, pointing through the sunset towards invisible headquarters. There, at the steady trot, was regiment after regiment, squadron after squadron, coming, coming, coming! It was just half-light, they were distinct yet indistinct. The Turkish guns blazed at those hazy horsemen but they came steadily on. At two miles distant they emerged from clouds of dust. Squadrons of men and horses taking shape. All the Turkish guns around Beersheba must have been directed at the menace then. Captured Turkish and German officers have told us that even then they never dreamed that mounted troops would be madmen enough to attempt rushing infantry redoubts protected by machine guns and artillery. At a mile distant their thousand hooves were stuttering thunder, coming at a rate that frightened a man – they were an awe-inspiring site, galloping through the red haze – knee to knee and horse to horse – the  dying sun glinting on bayonet-points. Machine gun and rifle fire just roared but the 4th brigade galloped on. We heard shouts among the thundering hooves, saw balls of flame amongst those hooves – horse after horse crashed, but the massed squadrons thundered on. We laughed in delight when the shells began bursting behind them telling that the gunners could not keep their range, then suddenly the men ceased to fall and we knew instinctively that the Turkish infantry, wild with excitement and fear, had forgotten to lower their rifle-sites and the bullets were flying overhead. The Turks did the same to us at El Quatia. The last half-mile was a berserk gallop with the squadrons in magnificent line, a heart-throbbing site as they plunged up the slope, the horses leaping the redoubt trenches – my glasses showed me the Turkish bayonets thrusting up the bellies of the horses – one regiment flung themselves from the saddle – we heard the mad shouts as the men jumped down into the trenches, a following regiment thundered over another redoubt, and to a triumphant roar of voices and hooves was galloping down the half-mile slope right into town. Then came a whirlwind of movement from all over the field, galloping batteries – dense dust from mounting regiments – a rush as troops poured from the opening in the gathering dark – mad, mad excitement – terrific explosions from down in the town.

dying sun glinting on bayonet-points. Machine gun and rifle fire just roared but the 4th brigade galloped on. We heard shouts among the thundering hooves, saw balls of flame amongst those hooves – horse after horse crashed, but the massed squadrons thundered on. We laughed in delight when the shells began bursting behind them telling that the gunners could not keep their range, then suddenly the men ceased to fall and we knew instinctively that the Turkish infantry, wild with excitement and fear, had forgotten to lower their rifle-sites and the bullets were flying overhead. The Turks did the same to us at El Quatia. The last half-mile was a berserk gallop with the squadrons in magnificent line, a heart-throbbing site as they plunged up the slope, the horses leaping the redoubt trenches – my glasses showed me the Turkish bayonets thrusting up the bellies of the horses – one regiment flung themselves from the saddle – we heard the mad shouts as the men jumped down into the trenches, a following regiment thundered over another redoubt, and to a triumphant roar of voices and hooves was galloping down the half-mile slope right into town. Then came a whirlwind of movement from all over the field, galloping batteries – dense dust from mounting regiments – a rush as troops poured from the opening in the gathering dark – mad, mad excitement – terrific explosions from down in the town.

Beersheba had fallen.2

There were 31 Australians who died in the charge of Beersheba, another 36 were wounded and 70 horses died. They captured over 700 prisoners. The son of a World War 1 veteran told me that his father was a farrier by trade. He prided himself in always being in command of a horse – except for one day. At the battle of Beersheba, his thirsty horse smelled the water and there was no way he could have stopped, even if he wanted to.

Endnotes:

- Gullet. H., Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918. Vol V11, Sinai and Palestine. Angus and Robertson, 1923, 395

- Idriess, I., The Desert Column, The Discovery Press, 1932, 251-252

Pictures:

- View from Tel el Saba (Tel Sheva) across the plains the ANZACs galloped – Jill Curry

- Disputed picture of the charge at Beersheba (or re-enactment) – Australian War memorial

https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/A02684/ It was probably taken when two regiments of the 4th Brigade, Australian Light Horse, re-enacted the charge for the official photographer Frank Hurley, at Belah on 7 February 1918. - Watering horses at Beersheba – Australian War Memorial

https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/P08548.001/ - Map of Beersheba – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Beersheba_(1917)

- Abraham’s Well tourist site (before renovations), Be’er Sheva – Jill Curry