Despite the success of gaining the Holy City there was still a threat from the north and the east. While the diggers spent the previous Christmas in the scorching desert, this Christmas was passed in driving rain and bone-chilling cold.

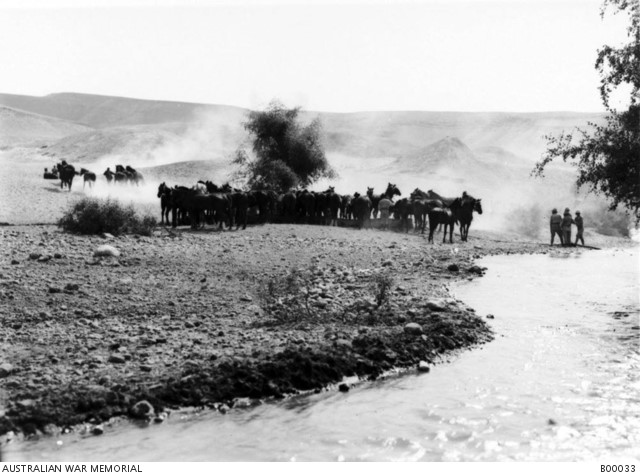

On December 26 and 27 the British troops were forced into battle by the Turks at ancient Gibeah but eventually prevailed. The next move was to take Jericho, one of the oldest cities in the world. In mid-February, the British troops began moving down the steep road through Wadi Qelt to the lowest place on earth. The ANZACs were assigned to take the treacherous valleys while the British faced the resistance down the well-trodden biblical Jericho road. The first to make it to the city of palms were the Australians of the ANZAC Mounted Division on February 21, 1918, but they were greeted not with a thriving city but with a squalid, smelly dump of a place. The retreating Turks crossed the Jordan and blew up the bridge which the Allies then had to replace with a makeshift pontoon bridge.

On March 21 the ANZACs and British troops were on the move again to attempt to take Amman and cut off the rail supply route running from Damascus into Saudi Arabia. Climbing up the steep sides of the rift valley is hard enough by car, let alone trying to do it on foot or horseback in the rain (or dark) following a goat track! By March 25 they had reached Es-Salt and captured that city despite the opposition being much less weary. The real target was Amman, which they reached by March 28. After several days of fighting they had not taken the citadel and were forced to retreat due to Turkish reinforcements arriving, the Arab backup not arriving to assist the Allies and a shortage of supplies. The effort cost 1,348 casualties with little gain except for 1,000 captured Turks. A second attempt followed on April 30-May 3, which again proved unsuccessful on several fronts, not the least being that once again the Arab reinforcements did not turn up. On this occasion, they did not get past Es-Salt. Another 1,600 casualties resulted. These broken promises from the Arab tribes further deteriorated the ANZACs’ low opinion of them. While the operations at Gaza had basically failed due to command error, the failure on this occasion was more due to the difficult terrain hampered by bad weather and a lack of reinforcements.

The Dead Sea is a wonderful place to visit and enjoy floating in the salty water in winter, but in summer the atmosphere can be oppressive. King Herod built his winter palace in Jericho for a good reason. It has sub-tropical temperatures where date palms grow, while the mountains of Israel 20 km above can be dressed in snow. The place for a summer palace was on a hilltop or by the sea not down 258 metres below sea level where the winds do not reach. Even the locals considered the valley uninhabitable in summer.

However, as summer approached, General Allenby wanted to keep a presence in the Jordan Valley to make the Turks believe that the assault would come from this easterly direction while he was actually planning to sweep up the coast on the west at the next opportunity. The ANZACs had to share their days living in tents with intense heat, scorpions, spiders, snakes, centipedes, and worst of all, malarial mosquitoes that bred in the swamps. Two hundred soldiers died of malaria and six to seven were hospitalised each day with the disease. There were still bombardments from German aircraft and occasional fire from snipers to look out for. To counter the horse lines being such easy targets, the ANZACs constructed wooden frames covered with hessian to look like horses from the air to fool the German pilots as to where the camps actually were. This novel idea worked to some extent.

However, as summer approached, General Allenby wanted to keep a presence in the Jordan Valley to make the Turks believe that the assault would come from this easterly direction while he was actually planning to sweep up the coast on the west at the next opportunity. The ANZACs had to share their days living in tents with intense heat, scorpions, spiders, snakes, centipedes, and worst of all, malarial mosquitoes that bred in the swamps. Two hundred soldiers died of malaria and six to seven were hospitalised each day with the disease. There were still bombardments from German aircraft and occasional fire from snipers to look out for. To counter the horse lines being such easy targets, the ANZACs constructed wooden frames covered with hessian to look like horses from the air to fool the German pilots as to where the camps actually were. This novel idea worked to some extent.

Some soldiers considered these hot, energy-sapping months the worst torture of the entire campaign. The diggers’ entertainment included setting up a contest between a scorpion and a deadly spider to see which would win the fight! The only positive was that they could dip in the Jordan River, if they could avoid sniper fire. By the end of summer they could not wait to leave the stifling, breezeless valley.

Some soldiers considered these hot, energy-sapping months the worst torture of the entire campaign. The diggers’ entertainment included setting up a contest between a scorpion and a deadly spider to see which would win the fight! The only positive was that they could dip in the Jordan River, if they could avoid sniper fire. By the end of summer they could not wait to leave the stifling, breezeless valley.

While the push into Palestine towards Amman had not succeeded militarily, it had achieved the aim strategically, since the Turks were still of the opinion that the next move would be on the eastern flank and were stationing their troops accordingly. Allenby still had the tactical advantage for what was to come.

Pictures:

- Dummy horses used to fool German aircraft –Australian War Memorial

https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/B02667/ - 4th Light Horse watering at the Jordan – Australian War Memorial

https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/B00033/